There’s an old Soviet joke that apparently arose at the time of Khrushchev’s 1956 “Secret Speech” to the Politburo, when he denounced Stalin’s crimes against the people. A child asks his mother, “Mama, was Lenin a good man?” “Yes,” says Mama, “Lenin was a good man.” “And Stalin, Mama, was Stalin a bad man?” “Yes,” says Mama, “it seems Stalin was a bad man.” After a pause the child asks, “What about Khrushchev, Mama, is Khrushchev a good man or a bad man?” And Mama answers, “We’ll have to wait till he dies to find out.”

When they took down the statues of great Soviet leaders after the fall of the USSR, most of the Lenin statues remained intact. A few were removed in the months immediately following the failed putsch of the old guard in August, 1991. But unlike Stalin, Dzerzhinsky, Brezhnev, and others, whose statues, in some cases defaced and broken, are now visible only in museums and museum archives, Lenin can still be seen, many times larger than life, in the midst of the squares, in front of imposing Stalin-era buildings, and even in the flesh, sort of, in the mausoleum on Red Square that bears his name.

The expanse of the former USSR and the near ubiquity of Lenin in ............

all its former republics make this an impressive, but also uncanny, aspect of contemporary post-Soviet life. Lenin founded the USSR, provided its first and most vibrant rationale for being, as a supra-national entity, and became the symbol most enduringly associated with it. It’s now been more than twenty years since the entity for which the symbol had stood ceased to exist. But travel anywhere from the Russian Far East to the Arctic Circle, through Central Asia, Siberia, and the Urals to the Caucasus and the Baltic Sea, and you won’t have to look far to find Lenin. Here he is standing in “classic” pose with hand outstretched, cap on head. There he has relaxed a bit, one hand in his pocket, the side of his long coat thrust back. Over there he’s obviously holding forth, his trench coat flying behind like the cape of a superhero. In granite, in marble, in snow, in rain, amid busy city traffic, at the entrance to national preserves, raised up high, or sitting at eyelevel, he is everywhere, across thirteen time zones.

When I asked my friend Vika why that still was, she exploded. “It’s an empty place!” she said, her eyes growing hard. “It might be interesting to you. Maybe it seems exotic. But to us it was life! Now it’s an empty place. That’s the only reason they haven’t ............

removed him. He doesn’t mean anything! They don’t think about him. You shouldn’t either!”

Vika is a successful, well-educated business woman who has lived in St. Petersburg, formerly Leningrad, all of her life. This has no doubt made her tenacious. I’ve known her for twenty-five years, and I knew well enough not to push her on the topic. She tends to add the word “place” to her adjectives, using the resulting phrases to describe sensations or ideas. If someone says something that seems stupid to her, it’s a stupid place. Something smart is a brilliant place. War veterans are a sacred place. You get the idea. It’s a feature of Russian, but also a way of categorizing things and making sense of them. So when she called Lenin an “empty place,” it occurred to me that she was making her own kind of sense of the phenomenon with her label, confining its importance, limiting it in a manner that contrasts sharply with the breadth of its physical reality. Lenin may be the most widely sculpted non-sacred figure in the world today, at least in the Northern Hemisphere. Calling him an empty place seemed at best a hope, at worst a denial.

Sitting next to her son Dima years before, as he flipped the pages ............

of one of his school books (He was eleven at the time, and this was in the late 1990s, not long after the fall of the USSR) he pointed to a picture and asked his mother, “Is this Lenin?” She saw my jaw drop open and winked at me. “Yes, Dima, that’s Lenin.” She didn’t scold him. Later she admitted it had bothered her at first that her son was not learning the same history that she and her generation, and even her daughter Marina, then twenty, had learned. But she’d gotten used to it quickly, she said. Everyone had. You find out after death if you’re right, she said, like about Khrushchev.

Dima had seen the statues of course, but he had not been taught to memorize the songs, the poems, the stories about Lenin as a schoolboy—little Volodya, always kind and considerate to teachers and classmates alike, bright and willing to help in any subject, hard-working to the point of asceticism, saintliness. Nor had he been taken to the “Lenin places,” pilgrimage sites of a sort, spread throughout the former Soviet Union, where Lenin gave a speech, or hid, or signed a document, or wrote a letter, or read a book, or did just about anything at all, and where generations of school children were taken on field trips to witness, if not to worship.

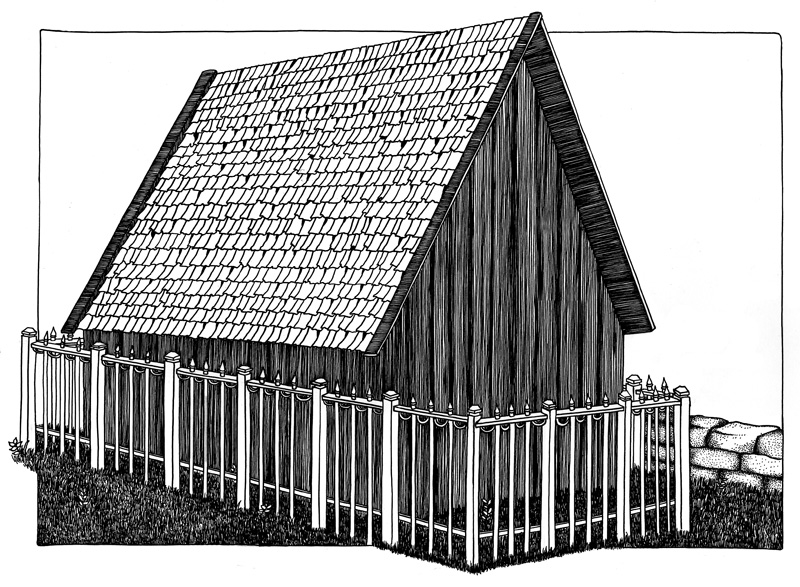

Vika wanted to show me what it had all meant, to her at least, so later that day we set out for Lenin’s “hut” and Lenin’s “barn,” two formerly holy sites in the semi-wilderness just northwest of Saint Petersburg. We quickly got lost. The way was no longer marked. We asked several people and eventually came to the barn by a footpath around a small lake surrounded by wooden dachas and bathhouses.

The barn is indeed a barn, a wooden structure probably intended for livestock or storing goods, in which Lenin hid from the police of the Provisional Government in the months following the February revolution of 1917. The entire structure is encased in clear hard plastic, like a specimen, sealed up without an entrance. The plaque on one of the barn’s outer walls says that this is where Lenin hid. There are dachas on all sides. I took some pictures and noticed that Vika had grown silent. On the way back to the car, she said it was smaller than she remembered.

The hut was in the midst of the forest, about two hundred yards from the water, on the other side of the razliv, or overflow from the Gulf of Finland. We parked the car in an enormous empty parking lot, large enough for dozens of school busses, the asphalt ............

cracked, potholes everywhere. There were what looked like concession stands at the entrance, but they were fenced in and boarded up, and the windows were broken. Plaques in several languages hung nearby, but I wasn’t able to make out any but a few words of the English, Italian, French, and German versions. The Russian had been burned out completely.

Two paved walkways led in different directions into the dense forest. There were no signs and no one was around to ask, so we took the one along the water and were nearly consumed by mosquitos within twenty paces. When we didn’t see the hut after ten minutes of walking—it seemed to Vika we should have arrived already—we asked a man and two children fishing on a small pier where Lenin’s hut was. They had no idea.

We turned and followed the path farther into the forest, silent but for the mosquitos’ buzzing, and the cicadas in the trees.

“There’s no one here,” Vika said, and then, her voice lower, as if responding to herself: “Of course there’s no one here.”

The hut was no longer standing. Under the Soviets the original ............

straw version had been rebuilt afresh every spring in a ritual reenactment of revolutionary rebirth. Then a solid granite “hut” had been built in the 1920s next to the location where the straw one reappeared every year. Finally a museum had been added in 1969, rounding off the complex, with its elaborate concession stands and ample parking lot, ready to receive busloads of boisterous Young Pioneers, ever at the ready.

We peeked through the museum window: the floor was strewn with assorted brushes and palettes, the space having been consigned to an aspiring artist as a summer studio, but he was nowhere to be seen.

On our way back to the car, Vika was quiet at first. Then she started to hum, and finally sang the words just loudly enough for me to make out.

“Lenin vsegda zhivoi,

Lenin vsegda so mnoi,

V gore, nadezhde i radosti.

Lenin v moei sud’be,

V kazhdom schastlivom dne.

Lenin v tebe i vo mne!”

(Lenin is always alive,

Lenin is always with me,

In sadness, hope, and joy.

Lenin is in my fate,

In every happy day.

Lenin is in me and in you!)

Her voice was small in the empty forest. Two cyclists rode toward us, looking us up and down quickly, and passed by.

She said it was a song from the fifties that she and all her friends had learned. She could only remember the chorus now, but that was enough.