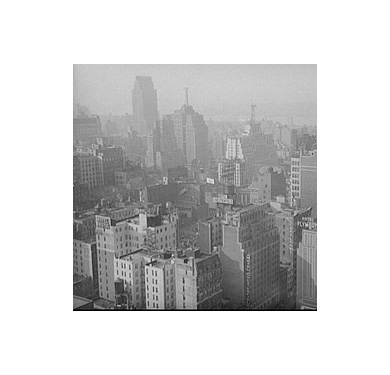

At the climax of the classic noir Naked City (1948), a frenetic handheld captures the sweep and rise of the Williamsburg Bridge in high-contrast black and white. Villain Willie the Harmonica gives frenzied chase from his Lower East Side crime lair, careering past rows of pickle and schmata vendors. The pushcarts erupt in a rain of knish, kugel, and women’s underwear as Harmonica ascends the bridge ramp and begins climbing. Up high now, he is dizzied by a moiré of bridge cables. The cinematography is stunning. He halts. His revolver catches a glint of daylight. Shots ring out. Poor Willie tumbles to the street below, and there meets his fateful end.

Whenever I watch this scene, a feeling comes over me at just that moment of moiré—a wash of exhilaration and longing.

“There are eight million stories in the naked city,” sounds a baritone voice-over. “This has been one of them.” It turns out the famous line, however, is less remembered for this movie than as the tagline for the television show created in its memory, the Naked City TV series (1958–1963). There’s something about that gap between the immortal memory of a thing and a thing itself that this post-hence TV series captures for me, a nostalgia turned in on itself. The original re-created becomes a fetish object to be remembered and re-remembered so many times it accrues one layer of memory atop another, so many overlays the image begins to warp and to dizzy the watcher, like sad Willie beneath the spell of those bridge cables.

Beginning a decade after the release of its namesake and running through four seasons, the Naked City TV series was arguably America’s first cop show. Its top writer, Sterling Silliphant, went on to become one of the wealthiest script men in Hollywood. And, like Twilight Zone, it gave a first run to many actors (and writers) who later went platinum: Robert Duvall; Christopher Walken, who was then Chris Walker; Jon Voight; Gene Hackman; Tuesday Weld; Jack Klugman; Dustin Hoffman; Martin Sheen; Walter Matthau; Vince Gardenia; William Shatner; Ed Asner; Peter Falk; Peter Fonda; Alan Alda. Paula Fox wrote an episode, and even Rocky Graziano made a cameo.

Naked City isn’t often talked about today, because, unlike Twilight Zone and other black-and-white contemporaries, it didn’t get picked up much in reruns. It gets mention from time to time alongside Dragnet and The Untouchables as a precursor to The Wire—gritty, urban, and hardboiled, with humanizing if mordant treatment of underworld lowlifes. Its Jimmy McNulty aka Dominic West is Adam Flint aka Paul Burke, a deeply flawed man in blue with eyes like perfect diamonds. Broken by a corrupt system, idealistic and sentimental, he performs his duty with full knowledge of the contingencies: a shattered legal apparatus, an existential emptiness in the notion of justice.

Flint ponders “the need to keep busy” in one episode told almost entirely in interior monologue, in which he must stand witness to an execution. “[L]ike this reporter next to me, making a detailed sketch of the chair, piling facts between himself and what he feels. Need in the other reporters, racing their pencils through their notebooks, trying to hold on to facts. How many doors are there in this room? How many feet from where we sit to where the warden stands? What have I to hold on to? What do I love?”

Like The Wire, the series traffics in noir staples—the “ambiguous protagonists” and “inglorious victims” codified in the famous 1955 French definition by theorists Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton. Its writing features the gum-cracking whimsy of Chandler: “It's two o'clock,” says a Vegas showgirl, upon waking to a Manhattan afternoon. “They get up so early here.” Roddy McDowall, playing a rep actor, is threatened with the line, “Keep away from his wife, or after I'm done with you the only thing your face will be able to play is the role of Frankenstein.” Also featured in this series is the kind of mesmerizing, chiaroscuro location shooting of the silver-screen precursors—in this case in New York City, age-old receptacle for melancholia and memory. The show certainly lays groundwork for neo-noir. Could we call it proto-neo-noir?

I discovered the Naked City series after I’d watched the eponymous movie, along with every great noir, and then all the Bs. I began suffering through Cs—for instance Detour, a story about a cross-country road trip in which the California line is crossed twice, and a corpse’s silken eyelashes can be seen to flutter. In one sequence cars drive on the left and the steering wheel rides shotgun, since the negative was flipped. Wretched cinematography nearly cured me of noir. The next refuge was television. I have since watched every episode available on DVD.

In conception the show is retro, late fifties and sixties pretending to be forties. It echoes and embraces the lost innocence of noir. And yet for Naked City’s time, noir might suddenly have looked naïve to these producers, a genre of happy endings and redeemed losers. Noir idealized criminals. In real life, there were traffic and road rage, city infrastructures unsuited for the growing metropolis, ethnic enclaves and the younger generation’s struggle to live between worlds, mixed-race communities and the assault on old-world values, deeper knowledge about the horrors of World War II, veterans and the prolonged social costs of war, geopolitical fallout from the bloody Indian Partition and the fraught start-up of Israel, Mayor John Lindsay’s war on peepshows and President Johnson’s war on porn, the Puerto Ricans versus the Italians, the blacks versus the Jews, the Poles versus everyone, beatniks, hippies, language poets.

To embrace the past was to willfully blot out the grittiness and modern irreconcilability of the postwar age, a mood better captured by the hysteria of Catch 22 or the apocalyptic confusion of Crying of Lot 49. There is something deeply unsettling in the way Naked City treads that slender line between noir and postmodern. It settles in for a cozy detour through the past, and then, in spite of itself, thrusts the viewer headlong into social realism, chaotic with the background noise of New York City. We see Jack Warden, for instance, as a war vet in the grip of bloody hallucinations, Alan Alda dressed in black turtleneck reading ear-damaging poetry at a club in the Village, Rip Torn going postal in a traffic jam.

For the viewer today, to become enchanted by this show is to indulge in a fantasy of return to several different time periods at once. There is its nostalgia fixed in its moment, a backward view that better reveals the maker than the thing made—a kind of inverse retro-futurism. Then, the nostalgia factors outwards. I watch a TV series memorializing a past-life movie that itself memorialized an even deeper past—an urban America of old-world immigrants. I wind up feeling longing for the era of the TV series, and also for each era echoed within it. The quintuple-vision creates an inversion, in which the subject winds up becoming nostalgia itself, more so than the thing for which it's nostalgic.

Is this what André Aciman was getting at when he made that coinage “palintropic,” a nostalgia that is always looping back on itself? Or is the condition of Naked City and those of us under its spell better explained by Samuel Delany's “nostalgia schema,” the idea that the first look is always the youthful look is always the best look? “Nostalgia,” he writes, “presupposes an uncritical confusion between the first, the best and the youthful gaze (through which we view the first and the best) with which we create origins.”

My own nostalgia is for a childhood of black-and-white reruns, for the first time I watched each great noir—with my father, with my aunt, now passed on—firsts I can’t get back to. Already I looked through many lenses. The movies meant something different for my relatives, who were children of World War II, and so, even then, had to be viewed in double or triple focus. When I watch Naked City I join a larger, more public nostalgia, one folded into the layers of the show’s own several pasts. If noir was an expression of Hemingway Modernism, what does that same vision look like when further refracted through the fragmentary gaze of post-moderns?

Where the show hits me deep is its New York City streetscapes, so irrevocably altered now. The show is a love note to New York. There is the Chrysler Building. There is the beautiful déco Cooper Station, where I keep my P.O. box. There is the St. Mark’s in the Bowery Church. Walking by that yesterday I noticed a statue in its courtyard featured in an episode dealing with alcoholism, its woeful protagonist pathetic and in a heap, crying at its feet. Aspiration, I see, is the name on the statue. There is that same street beneath the Williamsburg Bridge where Harmonica met his end. I see that streetscape every night outside my window. And my great-great-grandparents settled there exactly, in 1873. We have the address on their citizenship papers, Delancey and Allen, before there was even a bridge.

Why is New York so often the setting for this sort of twisted remembering, this nostalgia that fluxes inward and outward, forward and backward, somehow endlessly circling the present, a moving target itself? It lures us, New Yorkers, or those of us whom Aciman recognizes as fellow “temporizers.” The temporizer, he writes, “accesses time—life, if you wish—so obliquely and in such roundabout ways and gives the present so provisional and tenuous a status that the present, insofar as such a thing is conceivable, ceases to exist, or, to be more accurate, does not count. It is unavailable.” For this temporizer, even the present actually exists in a prefigured past: “He moves from the present to the future, from the present to the past… firm[ing] up the present by experiencing it from the future as a moment in the past.”

Of course the sentimental journey through Gotham lures the outlier also, that person who left, or whose parents or grandparents did, or whose great-grandparents came through Ellis. This might explain why Naked City was allowed its inconsistencies. In that bridge episode—in which Diahann Carroll plays a teacher for the blind whose young pupil, trying to prove himself, gets lost on his way to Brooklyn—the bridge is in one shot the Williamsburg, in another the Brooklyn. Who’s really watching? The producers are taunting us. The New York bridges are iconic, speaking the words New York bridge. No need to limit the location scouts. For the non-native, New York is not about the details. We insiders, so greedy for a fix, put up with anything.

I think of Lynne Tillman asking, “What is history for? What is remembering for?” She asks this of a New York art scene she was once a part of. “Being in the present entails having a past that is never completely dead and also never again alive.”

Naked City asks us to consider the ways we view our pasts as well, and the places real and imagined those pasts took place. One episode tells a story of a murderer who is so traumatized by the event, he has lost all memory of his deed. “Without memory you can’t have a conscience,” says the villain. “Without a conscience how can you feel guilty?” Naked City keeps New York, as much as it is ever-changing, fixed in a moment of flux. It is offered as a place of memory, that memory the idea itself. Rather than crime, or character, or whodunit, its subject becomes the fluid and uncertain quality of memory itself.